The Whanganui River

The Whanganui River is central to the existence of Whanganui Iwi and their health and wellbeing. The River has provided both physical and spiritual sustenance to Whanganui Iwi and its hapū from time immemorial.

The Whanganui River has acted from early times as an artery for Māori inhabiting its forests and fertile river terraces and travelling to and from the central North Island. There are numerous kāinga and pā sites, urupā and other wāhi tapu throughout the length of the River and there remain many active marae on the River today.

Other groups with interests in the parts of the Whanganui River and its tributaries include the iwi of Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Rereahu, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngā Rauru Kītahi and Ngāti Apa and certain of their hapū.

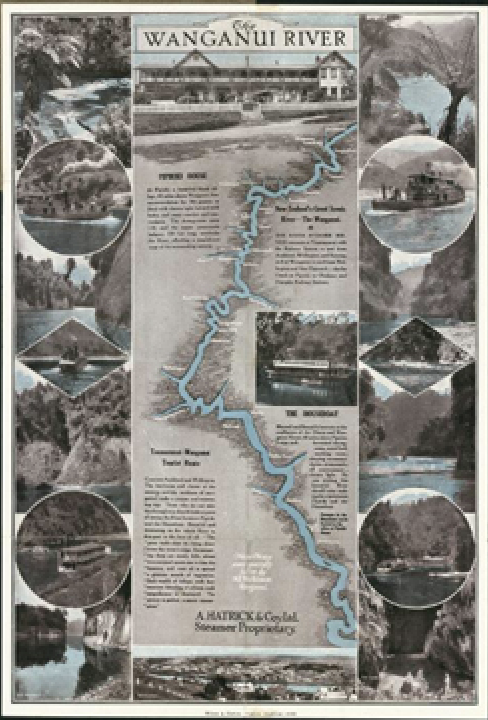

The Whanganui River is of significant national importance. It is New Zealand’s longest navigable river, stretching for 290km from the slopes of Mount Tongariro to the Tasman Sea. With its headwaters in the Tongariro National Park and bounded for much of its middle reaches by the Whanganui National Park, the Whanganui River has significant natural, scenic, and recreational values. It is an important habitat for indigenous fish and whio.

The River also plays an important role in power generation with waters diverted by the Tongariro Power Scheme from the River’s headwaters into Lake Taupō and on into the Waikato River contributing to the generation of approximately 5% of New Zealand’s electricity.

The issue of the ownership of the Whanganui River has been a longstanding focus of grievance for Whanganui Iwi. As at 1840 the iwi and hapū of Whanganui possessed and exercised rights and responsibilities in relation to, the Whanganui River in accordance with their tikanga.

Various statutes and actions of the Crown over more than 100 years have dramatically affected the legal ownership and management of the Whanganui River and the ability of Whanganui Iwi to exercise its full rights and responsibilities in relation to the River. The Coal-Mines Act Amendment Act 1903 declared that the beds of all navigable rivers “shall remain and shall be deemed to have always been vested in the Crown” and the Crown has considered the main stem of the Whanganui River from its mouth to Taumarunui at least to be navigable.

Despite this, the iwi and hapū of Whanganui have, over many generations since 1840, maintained the position that they never relinquished their rights and interests in the Whanganui River and have sought to protect and provide for their relationship with the Whanganui River in many ways.

Timeline of changes on the Whanganui River

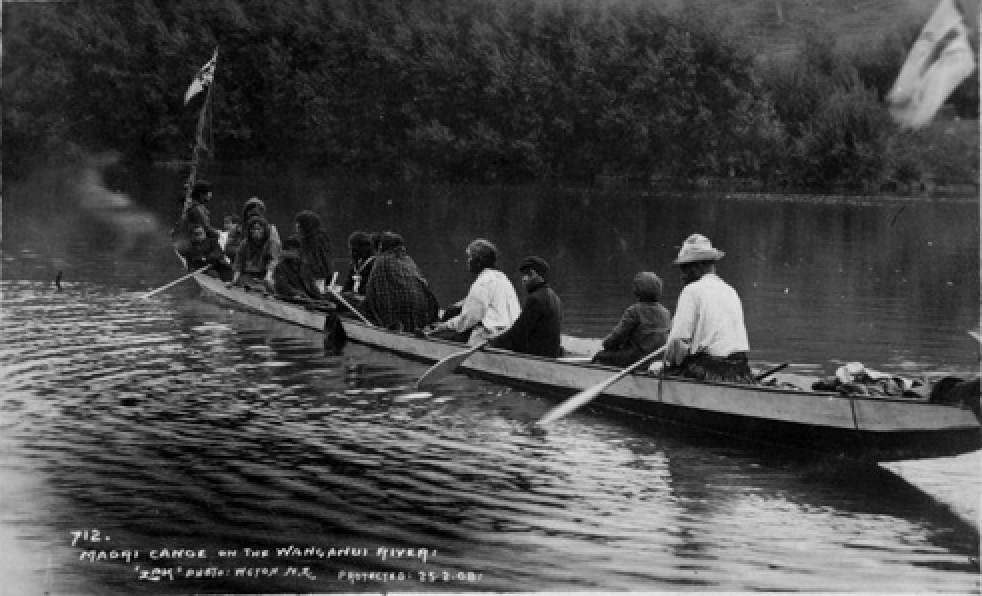

1886

1886 -1888 over 501 Iwi members petition the government to stop steamers destroying the pā tuna and utu piharau (lampery weirs)

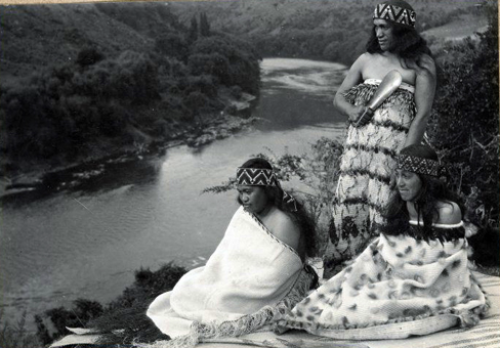

Image: Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

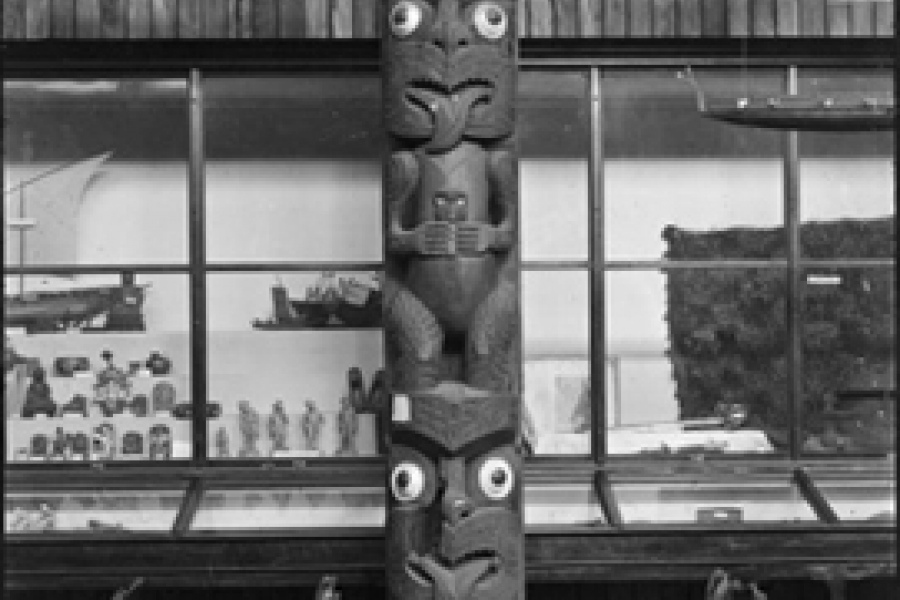

1895

Whanganui Iwi take claim to the Supreme Court over customary fishing rights. In 1896 the Whanganui River Trust Board (an agency of the Crown) is established, giving control of the River to the colonists.

Image: Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

1949

Judge Hay rules that the coal Mine Amendment Act of 1903 had given ownership of the bed of the River to the Crown. As a result the areas of the riverbed are deemed part and parcel to the sale of adjacent land blocks.

1950

A Royal Commission of Inquiry is established to determine whether Iwi customarily owned the riverbed. In 1955 the Court of Appeal finds the "the bed of the Whanganui River had been owned under the Maori custom"

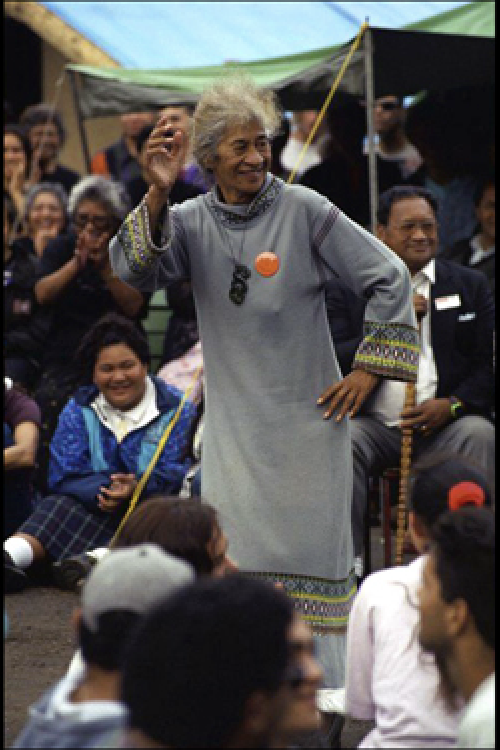

Image: Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

1986

The New Zealand Gazette establishes Water Control Orders over the Whanganui River.

The Whanganui National Park is established but excludes the River due to an Iwi petition.

The Minister of Lands promises Iwi participation in the running of the park, but fails to deliver.

1988

The Whanganui River Māori Trust Board is established to negotiate all outstanding claims relating to the customary rights of Whanganui Iwi.

In 1989 Iwi begin Te Tira Hoe Waka, an annual 2 week pilgrimage that revisits the sacred sites and Marae along the Whanganui River.

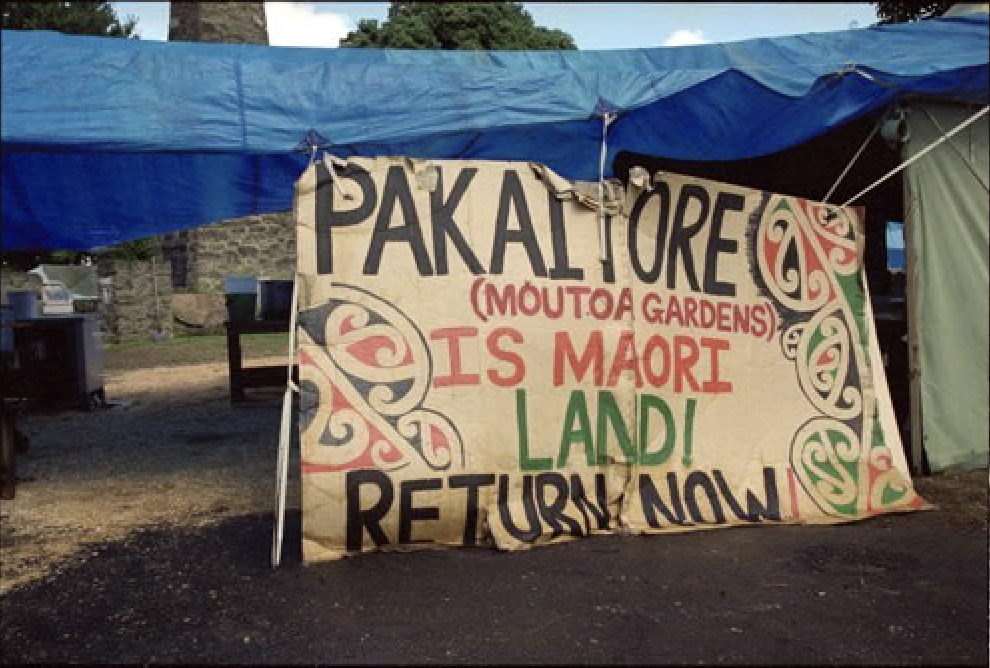

1995

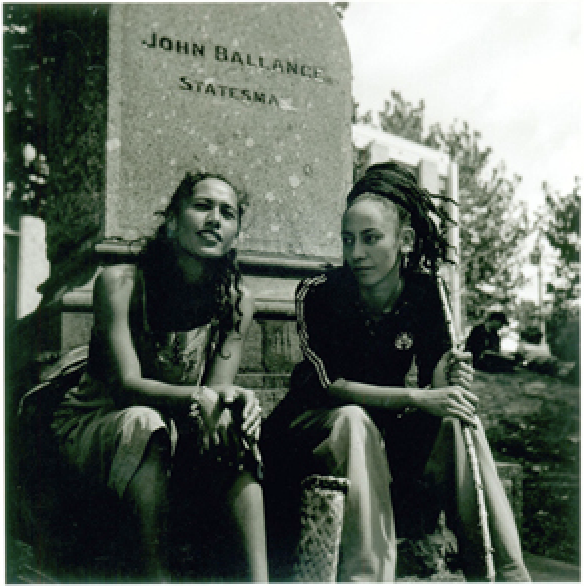

Whanganui Iwi occupy Pākaitore for 80 days, and then commemorate the event each year.

Pākaitore Occupation

Register

Do you whakapapa to the Whanganui River? Would you and your whānau like to be registered on the Whanganui Iwi Database? What does that mean?

It means that you get sent pānui and updates on kaupapa related to the Whanganui River and Te Awa Tupua, the people and the river from the Mountains to the Sea. You can also apply for the different grants that are advertised on our website and facebook page.

If you are already on the database and need to up date your details please head to the database or send us an email at office@ngatangatatiaki.co.nz